13 Relational data

13.1 Introduction

It’s rare that a data analysis involves only a single table of data. Typically you have many tables of data, and you must combine them to answer the questions that you’re interested in. Collectively, multiple tables of data are called relational data because it is the relations, not just the individual datasets, that are important.

Relations are always defined between a pair of tables. All other relations are built up from this simple idea: the relations of three or more tables are always a property of the relations between each pair. Sometimes both elements of a pair can be the same table! This is needed if, for example, you have a table of people, and each person has a reference to their parents.

To work with relational data you need verbs that work with pairs of tables. There are three families of verbs designed to work with relational data:

Mutating joins, which add new variables to one data frame from matching observations in another.

Filtering joins, which filter observations from one data frame based on whether or not they match an observation in the other table.

Set operations, which treat observations as if they were set elements.

The most common place to find relational data is in a relational database management system (or RDBMS), a term that encompasses almost all modern databases. If you’ve used a database before, you’ve almost certainly used SQL. If so, you should find the concepts in this chapter familiar, although their expression in pandas is a little different. Generally, pandas is a little easier to use than SQL because pandas is specialised to do data analysis: it makes common data analysis operations easier, at the expense of making it more difficult to do other things that aren’t commonly needed for data analysis.

13.1.1 Prerequisites

We will explore relational data from nycflights13 using the two-table verbs from dplyr.

import pandas as pd

import altair as alt

import numpy as np13.2 nycflights13

We will use the nycflights13 package to learn about relational data. nycflights13 contains four tibbles that are related to the flights table that you used in data transformation:

base_url = "https://github.com/byuidatascience/data4python4ds/raw/master/data-raw/"

flights = pd.read_csv("{}flights/flights.csv".format(base_url))

airlines = pd.read_csv("{}airlines/airlines.csv".format(base_url))

airports = pd.read_csv("{}airports/airports.csv".format(base_url))

planes = pd.read_csv("{}planes/planes.csv".format(base_url))

weather = pd.read_csv("{}weather/weather.csv".format(base_url))airlineslets you look up the full carrier name from its abbreviated code:airlines.head() #> carrier name #> 0 9E Endeavor Air Inc. #> 1 AA American Airlines Inc. #> 2 AS Alaska Airlines Inc. #> 3 B6 JetBlue Airways #> 4 DL Delta Air Lines Inc.airportsgives information about each airport, identified by thefaaairport code:airports.head() #> faa name lat ... tz dst tzone #> 0 04G Lansdowne Airport 41.130472 ... -5 A America/New_York #> 1 06A Moton Field Municipal Airport 32.460572 ... -6 A America/Chicago #> 2 06C Schaumburg Regional 41.989341 ... -6 A America/Chicago #> 3 06N Randall Airport 41.431912 ... -5 A America/New_York #> 4 09J Jekyll Island Airport 31.074472 ... -5 A America/New_York #> #> [5 rows x 8 columns]planesgives information about each plane, identified by itstailnum:planes.head() #> tailnum year type ... seats speed engine #> 0 N10156 2004.0 Fixed wing multi engine ... 55 NaN Turbo-fan #> 1 N102UW 1998.0 Fixed wing multi engine ... 182 NaN Turbo-fan #> 2 N103US 1999.0 Fixed wing multi engine ... 182 NaN Turbo-fan #> 3 N104UW 1999.0 Fixed wing multi engine ... 182 NaN Turbo-fan #> 4 N10575 2002.0 Fixed wing multi engine ... 55 NaN Turbo-fan #> #> [5 rows x 9 columns]weathergives the weather at each NYC airport for each hour:weather.head() #> origin year month day ... precip pressure visib time_hour #> 0 EWR 2013 1 1 ... 0.0 1012.0 10.0 2013-01-01T06:00:00Z #> 1 EWR 2013 1 1 ... 0.0 1012.3 10.0 2013-01-01T07:00:00Z #> 2 EWR 2013 1 1 ... 0.0 1012.5 10.0 2013-01-01T08:00:00Z #> 3 EWR 2013 1 1 ... 0.0 1012.2 10.0 2013-01-01T09:00:00Z #> 4 EWR 2013 1 1 ... 0.0 1011.9 10.0 2013-01-01T10:00:00Z #> #> [5 rows x 15 columns]

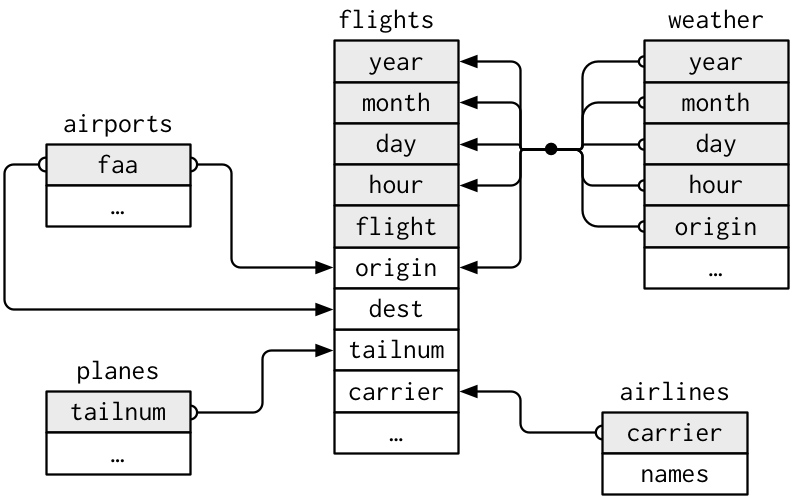

One way to show the relationships between the different tables is with a drawing:

This diagram is a little overwhelming, but it’s simple compared to some you’ll see in the wild! The key to understanding diagrams like this is to remember each relation always concerns a pair of tables. You don’t need to understand the whole thing; you just need to understand the chain of relations between the tables that you are interested in.

For nycflights13:

flightsconnects toplanesvia a single variable,tailnum.flightsconnects toairlinesthrough thecarriervariable.flightsconnects toairportsin two ways: via theoriginanddestvariables.flightsconnects toweatherviaorigin(the location), andyear,month,dayandhour(the time).

13.2.1 Exercises

Imagine you wanted to draw (approximately) the route each plane flies from its origin to its destination. What variables would you need? What tables would you need to combine?

I forgot to draw the relationship between

weatherandairports. What is the relationship and how should it appear in the diagram?weatheronly contains information for the origin (NYC) airports. If it contained weather records for all airports in the USA, what additional relation would it define withflights?We know that some days of the year are “special”, and fewer people than usual fly on them. How might you represent that data as a data frame? What would be the primary keys of that table? How would it connect to the existing tables?

13.3 Keys

The variables used to connect each pair of tables are called keys. A key is a variable (or set of variables) that uniquely identifies an observation. In simple cases, a single variable is sufficient to identify an observation. For example, each plane is uniquely identified by its tailnum. In other cases, multiple variables may be needed. For example, to identify an observation in weather you need five variables: year, month, day, hour, and origin.

There are two types of keys:

A primary key uniquely identifies an observation in its own table. For example,

planes.tailnumis a primary key because it uniquely identifies each plane in theplanestable.A foreign key uniquely identifies an observation in another table. For example,

flights.tailnumis a foreign key because it appears in theflightstable where it matches each flight to a unique plane.

A variable can be both a primary key and a foreign key. For example, origin is part of the weather primary key, and is also a foreign key for the airport table.

Once you’ve identified the primary keys in your tables, it’s good practice to verify that they do indeed uniquely identify each observation. One way to do that is to value_counts() the primary keys and look for entries where the count is greater than one:

planes.tailnum.value_counts().value_counts()

#> 1 3322

#> Name: tailnum, dtype: int64

(weather.

groupby(['year', 'month','day','hour', 'origin']).

size().reset_index(name = 'n').n.value_counts())

#> 1 26109

#> 2 3

#> Name: n, dtype: int64Sometimes a table doesn’t have an explicit primary key: each row is an observation, but no combination of variables reliably identifies it. For example, what’s the primary key in the flights table? You might think it would be the date plus the flight or tail number, but neither of those are unique:

(flights.

groupby(['year', 'month','day', 'flight']).

size().reset_index(name = 'n').n.value_counts())

#> 1 274398

#> 2 27029

#> 3 2636

#> 4 103

#> Name: n, dtype: int64

(flights.

groupby(['year', 'month','day', 'tailnum']).

size().reset_index(name = 'n').n.value_counts())

#> 1 186729

#> 2 49530

#> 3 12211

#> 4 2863

#> 5 78

#> Name: n, dtype: int64When starting to work with this data, I had naively assumed that each flight number would be only used once per day: that would make it much easier to communicate problems with a specific flight. Unfortunately that is not the case! If a table lacks a primary key, it’s sometimes useful to add one with mutate() and row_number(). That makes it easier to match observations if you’ve done some filtering and want to check back in with the original data. This is called a surrogate key.

A primary key and the corresponding foreign key in another table form a relation. Relations are typically one-to-many. For example, each flight has one plane, but each plane has many flights. In other data, you’ll occasionally see a 1-to-1 relationship. You can think of this as a special case of 1-to-many. You can model many-to-many relations with a many-to-1 relation plus a 1-to-many relation. For example, in this data there’s a many-to-many relationship between airlines and airports: each airline flies to many airports; each airport hosts many airlines.

13.3.1 Exercises

- Add a surrogate key to

flights.

13.4 Mutating joins

The first tool we’ll look at for combining a pair of tables is the mutating join. A mutating join allows you to combine variables from two tables. It first matches observations by their keys, then copies across variables from one table to the other.

Like assign(), the join functions add variables to the right, so if you have a lot of variables already, the new variables won’t get printed out. For these examples, we’ll make it easier to see what’s going on in the examples by creating a narrower dataset:

flights2 = flights.filter(['year','month', 'day','hour', 'origin', 'dest', 'tailnum', 'carrier'])

flights2

#> year month day hour origin dest tailnum carrier

#> 0 2013 1 1 5 EWR IAH N14228 UA

#> 1 2013 1 1 5 LGA IAH N24211 UA

#> 2 2013 1 1 5 JFK MIA N619AA AA

#> 3 2013 1 1 5 JFK BQN N804JB B6

#> 4 2013 1 1 6 LGA ATL N668DN DL

#> ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ...

#> 336771 2013 9 30 14 JFK DCA NaN 9E

#> 336772 2013 9 30 22 LGA SYR NaN 9E

#> 336773 2013 9 30 12 LGA BNA N535MQ MQ

#> 336774 2013 9 30 11 LGA CLE N511MQ MQ

#> 336775 2013 9 30 8 LGA RDU N839MQ MQ

#>

#> [336776 rows x 8 columns](Remember, when you’re in VS Code, you can also use the data viewer to avoid this problem.)

Imagine you want to add the full airline name to the flights2 data. You can combine the airlines and flights2 data frames with merge() using how = 'left':

(flights2.

merge(airlines, on = 'carrier', how = 'left').

drop(columns = ['origin', 'dest']))

#> year month day hour tailnum carrier name

#> 0 2013 1 1 5 N14228 UA United Air Lines Inc.

#> 1 2013 1 1 5 N24211 UA United Air Lines Inc.

#> 2 2013 1 1 5 N619AA AA American Airlines Inc.

#> 3 2013 1 1 5 N804JB B6 JetBlue Airways

#> 4 2013 1 1 6 N668DN DL Delta Air Lines Inc.

#> ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ...

#> 336771 2013 9 30 14 NaN 9E Endeavor Air Inc.

#> 336772 2013 9 30 22 NaN 9E Endeavor Air Inc.

#> 336773 2013 9 30 12 N535MQ MQ Envoy Air

#> 336774 2013 9 30 11 N511MQ MQ Envoy Air

#> 336775 2013 9 30 8 N839MQ MQ Envoy Air

#>

#> [336776 rows x 7 columns]The result of joining airlines to flights2 is an additional variable: name. The following sections explain, in detail, how mutating joins work. You’ll start by learning a useful visual representation of joins. We’ll then use that to explain the four mutating join functions: the inner join, and the three outer joins. When working with real data, keys don’t always uniquely identify observations, so next we’ll talk about what happens when there isn’t a unique match. Finally, you’ll learn how to tell dplyr which variables are the keys for a given join.

13.4.1 Understanding joins

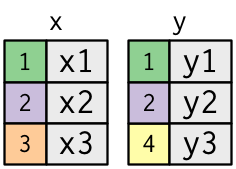

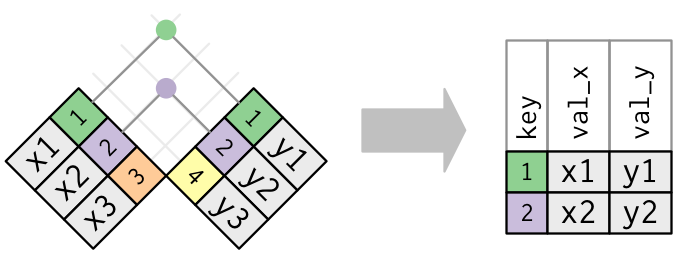

To help you learn how joins work, I’m going to use a visual representation:

x = pd.DataFrame({

'key': [1,2,3],

'val_x': ['x1', 'x2', 'x3']})

y = pd.DataFrame({

'key': [1,2,3],

'val_y': ['y1', 'y2', 'y3']})The coloured column represents the “key” variable: these are used to match the rows between the tables. The grey column represents the “value” column that is carried along for the ride. In these examples I’ll show a single key variable, but the idea generalises in a straightforward way to multiple keys and multiple values.

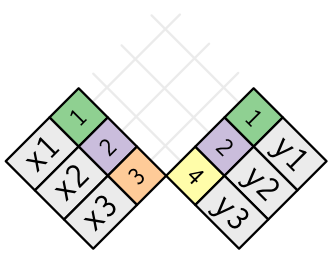

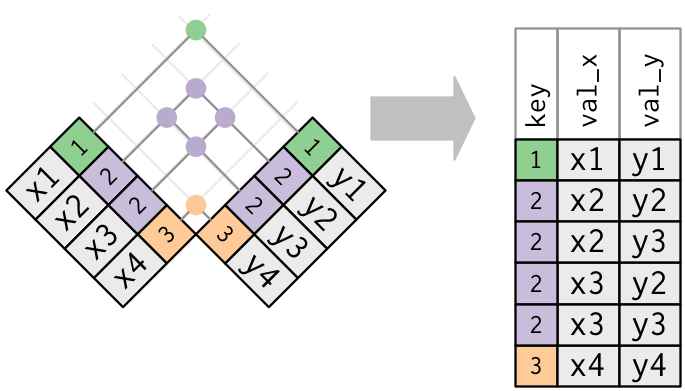

A join is a way of connecting each row in x to zero, one, or more rows in y. The following diagram shows each potential match as an intersection of a pair of lines.

(If you look closely, you might notice that we’ve switched the order of the key and value columns in x. This is to emphasise that joins match based on the key; the value is just carried along for the ride.)

In an actual join, matches will be indicated with dots. The number of dots = the number of matches = the number of rows in the output.

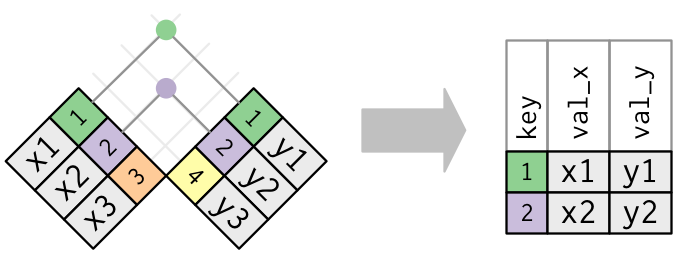

13.4.2 Inner join

The simplest type of join is the inner join. An inner join matches pairs of observations whenever their keys are equal using the argument how = 'inner':

(To be precise, this is an inner equijoin because the keys are matched using the equality operator. Since most joins are equijoins we usually drop that specification.)

The output of an inner join is a new data frame that contains the key, the x values, and the y values. We use by to tell dplyr which variable is the key:

x.merge(y, on = 'key', how = 'inner')

#> key val_x val_y

#> 0 1 x1 y1

#> 1 2 x2 y2

#> 2 3 x3 y3The most important property of an inner join is that unmatched rows are not included in the result. This means that generally inner joins are usually not appropriate for use in analysis because it’s too easy to lose observations.

13.4.3 Outer joins

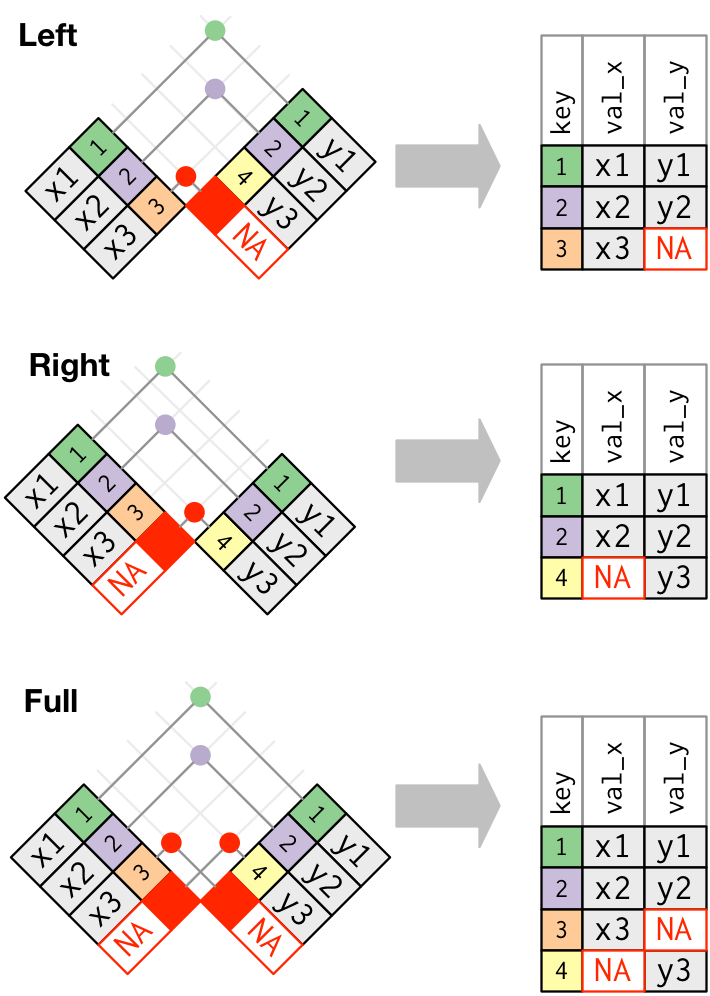

An inner join keeps observations that appear in both tables. An outer join keeps observations that appear in at least one of the tables. There are three types of outer joins:

- A left join keeps all observations in

xusinghow = 'left'. - A right join keeps all observations in

yusinghow = 'right'. - A full join keeps all observations in

xandyusinghow = 'full'.

These joins work by adding an additional “virtual” observation to each table. This observation has a key that always matches (if no other key matches), and a value filled with NA.

Graphically, that looks like:

The most commonly used join is the left join: you use this whenever you look up additional data from another table, because it preserves the original observations even when there isn’t a match. The left join should be your default join: use it unless you have a strong reason to prefer one of the others.

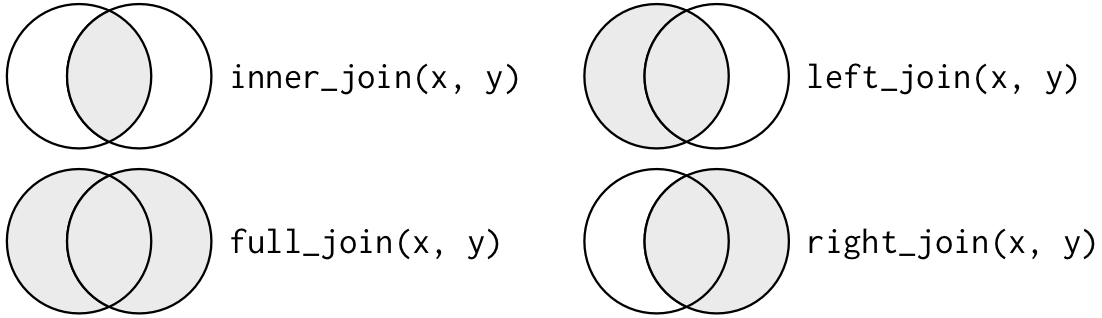

Another way to depict the different types of joins is with a Venn diagram:

However, this is not a great representation. It might jog your memory about which join preserves the observations in which table, but it suffers from a major limitation: a Venn diagram can’t show what happens when keys don’t uniquely identify an observation.

13.4.4 Duplicate keys

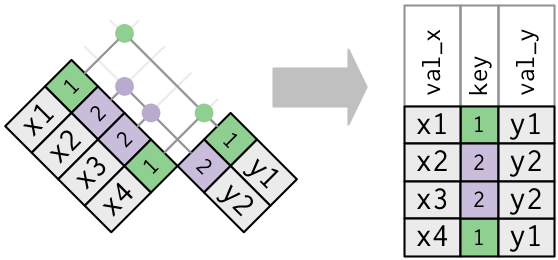

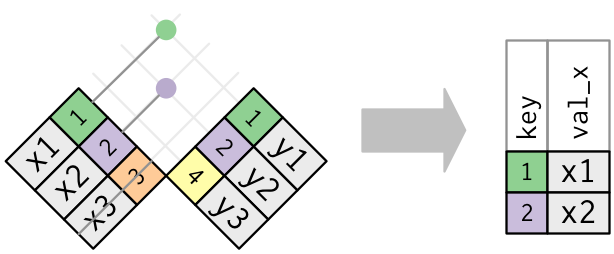

So far all the diagrams have assumed that the keys are unique. But that’s not always the case. This section explains what happens when the keys are not unique. There are two possibilities:

One table has duplicate keys. This is useful when you want to add in additional information as there is typically a one-to-many relationship.

Note that I’ve put the key column in a slightly different position in the output. This reflects that the key is a primary key in

yand a foreign key inx.x = pd.DataFrame({ 'key': [1, 2, 2, 1], 'val_x': ['x1', 'x2', 'x3', 'x4']}) y = pd.DataFrame({ 'key': [1,2], 'val_y': ['y1', 'y2']}) x.merge(y, on = 'key', how = 'left') #> key val_x val_y #> 0 1 x1 y1 #> 1 2 x2 y2 #> 2 2 x3 y2 #> 3 1 x4 y1Both tables have duplicate keys. This is usually an error because in neither table do the keys uniquely identify an observation. When you join duplicated keys, you get all possible combinations, the Cartesian product:

x = pd.DataFrame({ 'key': [1, 2, 2, 1], 'val_x': ['x1', 'x2', 'x3', 'x4']}) y = pd.DataFrame({ 'key': [1,2], 'val_y': ['y1', 'y2']}) x.merge(y, on = 'key', how = 'left') #> key val_x val_y #> 0 1 x1 y1 #> 1 2 x2 y2 #> 2 2 x3 y2 #> 3 1 x4 y1

13.4.5 Defining the key columns

So far, the pairs of tables have always been joined by a single variable, and that variable has the same name in both tables. That constraint was encoded by on = "key". You can use other values for on to connect the tables in other ways:

The default,

by = NULL, uses all variables that appear in both tables, the so called natural join. The defaulthowis left join. For example, the flights and weather tables match on their common variables:year,month,day,hourandorigin.flights2.merge(weather) #> year month day hour ... precip pressure visib time_hour #> 0 2013 1 1 5 ... 0.0 1011.9 10.0 2013-01-01T10:00:00Z #> 1 2013 1 1 5 ... 0.0 1011.9 10.0 2013-01-01T10:00:00Z #> 2 2013 1 1 5 ... 0.0 1011.4 10.0 2013-01-01T10:00:00Z #> 3 2013 1 1 5 ... 0.0 1012.1 10.0 2013-01-01T10:00:00Z #> 4 2013 1 1 5 ... 0.0 1012.1 10.0 2013-01-01T10:00:00Z #> ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... #> 335215 2013 9 30 22 ... 0.0 1016.5 10.0 2013-10-01T02:00:00Z #> 335216 2013 9 30 22 ... 0.0 1016.5 10.0 2013-10-01T02:00:00Z #> 335217 2013 9 30 22 ... 0.0 1016.5 10.0 2013-10-01T02:00:00Z #> 335218 2013 9 30 22 ... 0.0 1016.5 10.0 2013-10-01T02:00:00Z #> 335219 2013 9 30 23 ... 0.0 1016.3 10.0 2013-10-01T03:00:00Z #> #> [335220 rows x 18 columns]A character vector,

on = "x". This is like a natural join, but uses only some of the common variables. For example,flightsandplaneshaveyearvariables, but they mean different things so we only want to join bytailnum. If you have two variables then you can useon = ["x", "y"]flights2.merge(planes, on = 'tailnum') #> year_x month day hour ... engines seats speed engine #> 0 2013 1 1 5 ... 2 149 NaN Turbo-fan #> 1 2013 1 8 14 ... 2 149 NaN Turbo-fan #> 2 2013 1 9 7 ... 2 149 NaN Turbo-fan #> 3 2013 1 9 11 ... 2 149 NaN Turbo-fan #> 4 2013 1 13 8 ... 2 149 NaN Turbo-fan #> ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... #> 284165 2013 9 20 18 ... 2 80 NaN Turbo-fan #> 284166 2013 9 22 18 ... 2 80 NaN Turbo-fan #> 284167 2013 9 23 18 ... 2 80 NaN Turbo-fan #> 284168 2013 9 24 18 ... 2 80 NaN Turbo-fan #> 284169 2013 9 28 7 ... 2 149 NaN Turbo-fan #> #> [284170 rows x 16 columns]Note that the

yearvariables (which appear in both input data frames, but are not constrained to be equal) are disambiguated in the output with a suffix.A character vector:

left_on = "a"andright_on = "b"``. This will match variableain tablexto variablebin tabley. The variables fromx` will be used in the output.For example, if we want to draw a map we need to combine the flights data with the airports data which contains the location (

latandlon) of each airport. Each flight has an origin and destinationairport, so we need to specify which one we want to join to:flights2.merge(airports, left_on = 'dest', right_on = 'faa') #> year month day hour ... alt tz dst tzone #> 0 2013 1 1 5 ... 97 -6 A America/Chicago #> 1 2013 1 1 5 ... 97 -6 A America/Chicago #> 2 2013 1 1 6 ... 97 -6 A America/Chicago #> 3 2013 1 1 7 ... 97 -6 A America/Chicago #> 4 2013 1 1 7 ... 97 -6 A America/Chicago #> ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. .. ... #> 329169 2013 8 3 16 ... 152 -9 A America/Anchorage #> 329170 2013 8 10 16 ... 152 -9 A America/Anchorage #> 329171 2013 8 17 16 ... 152 -9 A America/Anchorage #> 329172 2013 8 24 16 ... 152 -9 A America/Anchorage #> 329173 2013 7 27 1 ... 22 -5 A America/New_York #> #> [329174 rows x 16 columns] flights2.merge(airports, left_on = 'origin', right_on = 'faa') #> year month day hour origin ... lon alt tz dst tzone #> 0 2013 1 1 5 EWR ... -74.168667 18 -5 A America/New_York #> 1 2013 1 1 5 EWR ... -74.168667 18 -5 A America/New_York #> 2 2013 1 1 6 EWR ... -74.168667 18 -5 A America/New_York #> 3 2013 1 1 6 EWR ... -74.168667 18 -5 A America/New_York #> 4 2013 1 1 6 EWR ... -74.168667 18 -5 A America/New_York #> ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. .. .. ... #> 336771 2013 9 30 22 JFK ... -73.778925 13 -5 A America/New_York #> 336772 2013 9 30 22 JFK ... -73.778925 13 -5 A America/New_York #> 336773 2013 9 30 22 JFK ... -73.778925 13 -5 A America/New_York #> 336774 2013 9 30 23 JFK ... -73.778925 13 -5 A America/New_York #> 336775 2013 9 30 14 JFK ... -73.778925 13 -5 A America/New_York #> #> [336776 rows x 16 columns]

13.4.6 Exercises

Add the location of the origin and destination (i.e. the

latandlon) toflights.Is there a relationship between the age of a plane and its delays?

What weather conditions make it more likely to see a delay?

13.4.7 Other implementations

The pandas user guide on Merge, join, and concatenate provides documentation on joining using and index.

SQL is the inspiration for pandas merge() function, so the translation is straightforward:

| dplyr | SQL |

|---|---|

x.merge(y, on = 'z', how = 'inner') |

SELECT * FROM x INNER JOIN y USING (z) |

x.merge(y, on = 'z', how = 'left') |

SELECT * FROM x LEFT OUTER JOIN y USING (z) |

x.merge(y, on = 'z', how = 'right') |

SELECT * FROM x RIGHT OUTER JOIN y USING (z) |

x.merge(y, on = 'z', how = 'outer') |

SELECT * FROM x FULL OUTER JOIN y USING (z) |

Note that “INNER” and “OUTER” are optional, and often omitted.

Joining different variables between the tables, e.g. x.merge(y, how = 'inner', left_on = 'a', right_on = 'b') uses a slightly different syntax in SQL: SELECT * FROM x INNER JOIN y ON x.a = y.b. As this syntax suggests, SQL supports a wider range of join types than pandas because you can connect the tables using constraints other than equality (sometimes called non-equijoins).

13.5 Filtering joins

Filtering joins match observations in the same way as mutating joins, but affect the observations, not the variables. There are two types:

- semi joins keeps all observations in

xthat have a match iny. - anti joins drops all observations in

xthat have a match iny.

Semi-joins are useful for matching filtered summary tables back to the original rows. For example, imagine that you’d found the 10 days with highest average delays. How would you construct the filter statement that used year, month, and day to match it back to flights?

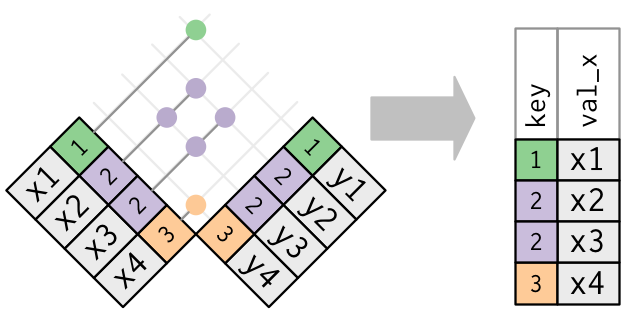

Instead you can use a semi-joins, which connects the two tables like a mutating join, but instead of adding new columns, only keeps the rows in x that have a match in y:

Graphically, a semi-join looks like this:

Only the existence of a match is important; it doesn’t matter which observation is matched. This means that filtering joins never duplicate rows like mutating joins do:

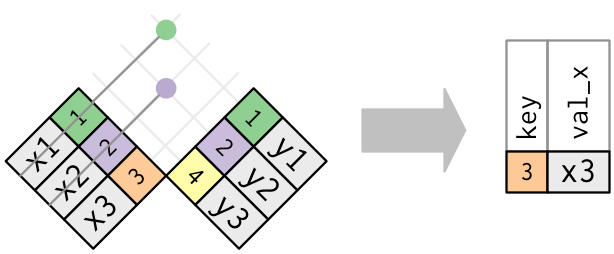

The inverse of a semi-join is an anti-join. An anti-join keeps the rows that don’t have a match:

Anti-joins are useful for diagnosing join mismatches. For example, when connecting flights and planes, you might be interested to know that there are many flights that don’t have a match in planes:

the pandas merge arguments don’t handle these two types of joins. However you can use pandas to get the same results. Anti-Join Pandas on stackoverflow provides a guide.

13.5.1 Exercises

What does it mean for a flight to have a missing

tailnum? What do the tail numbers that don’t have a matching record inplaneshave in common? (Hint: one variable explains ~90% of the problems.)Filter flights to only show flights with planes that have flown at least 100 flights.

Find the 48 hours (over the course of the whole year) that have the worst delays. Cross-reference it with the

weatherdata. Can you see any patterns?You might expect that there’s an implicit relationship between plane and airline, because each plane is flown by a single airline. Confirm or reject this hypothesis using the tools you’ve learned above.

13.6 Join problems

The data you’ve been working with in this chapter has been cleaned up so that you’ll have as few problems as possible. Your own data is unlikely to be so nice, so there are a few things that you should do with your own data to make your joins go smoothly.

Start by identifying the variables that form the primary key in each table. You should usually do this based on your understanding of the data, not empirically by looking for a combination of variables that give a unique identifier. If you just look for variables without thinking about what they mean, you might get (un)lucky and find a combination that’s unique in your current data but the relationship might not be true in general.

For example, the altitude and longitude uniquely identify each airport, but they are not good identifiers!

airports.groupby(['alt', 'lon']).size().value_counts() #> 1 1458 #> dtype: int64Check that none of the variables in the primary key are missing. If a value is missing then it can’t identify an observation!

Check that your foreign keys match primary keys in another table. It’s common for keys not to match because of data entry errors. Fixing these is often a lot of work.

If you do have missing keys, you’ll need to be thoughtful about your use of inner vs. outer joins, carefully considering whether or not you want to drop rows that don’t have a match.

Be aware that simply checking the number of rows before and after the join is not sufficient to ensure that your join has gone smoothly. If you have an inner join with duplicate keys in both tables, you might get unlucky as the number of dropped rows might exactly equal the number of duplicated rows!