4 Workflow: basics

You now have some experience running Python code. I didn’t give you many details, but you’ve obviously figured out the basics, or you would’ve thrown this book away in frustration! Frustration is natural when you start programming in Python, because it is such a stickler for punctuation, and even one character out of place will cause it to complain. But while you should expect to be a little frustrated, take comfort in that it’s both typical and temporary: it happens to everyone, and the only way to get over it is to keep trying.

Before we go any further, let’s make sure you’ve got a solid foundation in running Python code, and that you know about some of the most helpful VS Code features.

4.1 Coding basics

Let’s review some basics we’ve so far omitted in the interests of getting you plotting as quickly as possible. You can use Python as a calculator:

1 / 200 * 30

#> 0.15

(59 + 73 + 2) / 3

#> 44.666666666666664You can create new objects with =:

x = 3 * 4All Python statements where you create objects, assignment statements, have the same form:

object_name = valueWhen reading that code say “object name gets value” in your head. You will make lots of assignments in data science Python programming. It is also good code formatting practice to wrap = with spaces. Code is miserable to read on a good day, so giveyoureyesabreak and use spaces.

4.2 What’s in a name?

Object names must start with a letter, and can only contain letters, numbers, and _. You cannot use . like R. You want your object names to be descriptive, so you’ll need a convention for multiple words. Python coding conventions recommend snake_case where you separate lowercase words with _.

i_use_snake_case

otherPeopleUseCamelCase

some.people.use.periods

And_aFew.People_RENOUNCEconventionWe’ll come back to code style later, in [functions].

You can inspect an object by typing its name:

x

#> 12Make another assignment:

this_is_a_really_long_name = 2.5To inspect this object, try out VS Codes completion facility: type “this_”, pause, add characters until you have a unique prefix, then press shift + return.

Make yet another assignment:

python_rocks = 2 ^ 3Let’s try to inspect it:

python_rock

#> ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

#> NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

#> ~.../python4ds_practice.py in

#> ----> 1 python_rock

#> NameError: name 'python_rock' is not defined

Python_rocks

#> ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

#> NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

#> ~.../python4ds_practice.py in

#> ----> 1 Python_rocks

#> NameError: name 'Python_rocks' is not definedThere’s an implied contract between you and Python: it will do the tedious computation for you, but in return, you must be completely precise in your instructions. Typos matter. Case matters.

4.3 Calling functions

Python does not have a large collection of built-in mathematical and statistical functions. You will need to use pandas, numpy, scikit-learn, and statsmodels to get the suite of functions for working and modeling with data.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import sklearn as sk

import statsmodels.api as sm Functions are called like this:

<AS PACKAGE NAME>.function_name(arg1 = val1, arg2 = val2, ...)Let’s try using np.arange() which returns regular arangement of numbers and, while we’re at it, learn more helpful features of intellisense in VS code. Type np.ar and pause. A popup shows you possible completions. Specify np.arange() by typing more (a “ange”) to disambiguate, or by using ↑/↓ arrows to select. If you hover over np.arange or type np.arange() a floating tooltip pops up, reminding you of the function’s arguments and purpose. If you want more help, can scroll through the arguments tool tip with your mouse.

VS Code will add matching opening (() and closing ()) parentheses for you. Type the arguments 1, 10 and hit return.

np.arange(1,10)

#> array([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9])Type this code and notice you get similar assistance with the paired quotation marks:

x = "hello world"Quotation marks and parentheses must always come in a pair. VS Code does its best to help you, but it’s still possible to mess up and end up with a mismatch.

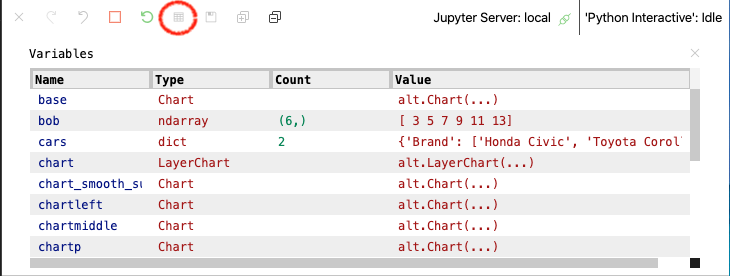

Now look at your Python interactive environment in VS Code in the top toolbar by selecting the icon circled in red :

Here you can see all of the objects that you’ve created.

4.4 Exercises

Why does this code not work?

my_variable <- 10 #> Error in py_call_impl(callable, dots$args, dots$keywords): NameError: name 'my_variable' is not defined #> #> Detailed traceback: #> File "<string>", line 1, in <module> my_varıable #> Error in py_call_impl(callable, dots$args, dots$keywords): NameError: name 'my_varıable' is not defined #> #> Detailed traceback: #> File "<string>", line 1, in <module>Look carefully! (This may seem like an exercise in pointlessness, but training your brain to notice even the tiniest difference will pay off when programming.)

Navigate to Visual Studio Code keyboard shortcuts by going to the menu under File > Preferences > Keyboard Shortcuts. (Code > Preferences > Keyboard Shortcuts on macOS). What do you see? You can read more about keybindings on the VS Code website.